KARACHI:

“Ishq-e-Mamnoon” came, aired and gloriously conquered the Pakistani drama industry. It was a bold and risky idea to air a translated series on national television but the drama received unexpectedly high ratings from the local audience.

The Urdu translation of this Turkish soap is considered to be infectious by its viewers and while some Pakistani writers, directors, and producers take it as a healthy competition, others believe it’s a grave threat.

“Our local production standards are very low; if we don’t raise them then in no time these dramas can eat us up,” says Rashid Khwaja — President of United Producers’ Association (UPA). “However, stopping the influx of foreign content is not the solution,” Khwaja tells The Express Tribune.

“The consumer will not let it happen because now we live in a global village and he will find access to it somehow but the stakeholders need to sit down and develop a new model of ‘high-scale drama production’ that is economically feasible to both, the producer and the channel,” says Khwaja.

Globally there are two TV models; “Ishq-e-Mamnoon” falls into the model in which producers hold he rights to the drama and recover the cost after airing them in their own country first. After cost recovery, the drama is available for other countries at a very low rate which is when the profit rolls in. The other model is what India follows. The channels, instead of producers, invest in a big scale production and become sole owners of the project.

Pakistan, however, doesn’t follow either model. The production houses make serials for approximately 6 lacs per episode and sell it to the channel for a profit of up to 2 lacs per episode; making the producer’s profit significantly low. This scenario results in more and more low quality entertainment for the channels.

TV director Azfar Ali, best known for sitcom “Sab set hai,” says that it’s not always about the size of a production. “I think the arrival of these soaps should give us a chance to boost our own industry standards,” says Ali. “Frankly speaking, it’s a pleasant change in time of a vacuum.” Ali believes it’s a matter of taking risks. He disagrees with the theory that investing more or giving producers the rights of the drama is going to change anything.

“You’ll laugh if I tell you the budget of ‘Sab Set Hai,’ but it changed your language — right?” asks Ali with a laugh. “The problem is that the producers now rely too much on research to get the ratings and play it very safe; but the ones who takes risks pose a threat to the status quo.”

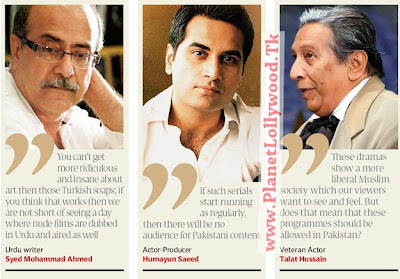

Renowned Urdu writer Syed Mohammad Ahmed believes that the Turkish soaps are not only a threat to the drama industry, but also to Pakistani culture.“This is absolute cheating with the local drama industry!” says Ahmed. “You can’t get more ridiculous and insane about art then those Turkish soaps; if you think that works then we are not short of seeing a day where nude films are dubbed in Urdu and aired as well.”

“If things go on like this, then it won’t take much time for Pakistani artists to go jobless,” says Ahmed.

On the other hand, veteran television and stage writer-director Khalid Ahmed says he is glad that better quality programming is being broadcast in Pakistan; however, he also thinks that the rest of the Turkish soaps will not be as popular.

Khalid says the ratings of the Turkish soap didn’t shock him. “It didn’t surprise me at all. ‘Ishq-e-Mamnoon’ is a mega hit all over the Middle East; but to say that more Turkish soaps will have the same impact is naïve because there is a huge cultural barrier that would eventually come in to play,” says Khalid.

On the other hand, senior actor Talat Hussain believes otherwise. “These dramas show a more liberal Muslim society which our viewers want to see and feel,” says Hussain “But does that mean that these programmes should be allowed in Pakistan? Certainly not — until or unless a dubbed Pakistani drama is playing in Turkey.” Hussain also added that the cultural similarity is going to cost us.

One of the leading actors and producers in the country, Humayun Saeed, believes that not only are the producers suffering, but a coffin is also being prepared for the leading actors in the country. “Since Shahrukh Khan is the biggest actor in Pakistan, whatever remains of TV stardom will be engulfed by these Turkish serials,” says Saeed. “I don’t want to see a future where I am going to do voice acting on someone else’s face; that is simply outrageous!”

His main concern is that the drama industry was the only industry that has continuously flourished. “If such serials start running regularly, then there will be no audience for Pakistani content,” said Saeed.

The professionals of the Pakistani drama industry have mixed opinions on what can be considered the biggest foreign invasion on Pakistani television since the Star Plus soaps. But they do agree that foreign soaps may end their careers, invade their industry and influence Pakistani culture.